The kids from Parkland were a major story all trough 2018 - from Valentines day to the mid term elections on November 6th. I have been following many of them since February. They have inspired me in many ways.

Today Carol and I received a flyer in the mail from our local Member of Parliament asking our opinion of Andrew Sheer's attempt to repeal Bill C-71. This is Canada's bill to provide reasonable background checks for those wishing to purchase firearms. I am completely in support of keeping C-71 in place and enhancing it.

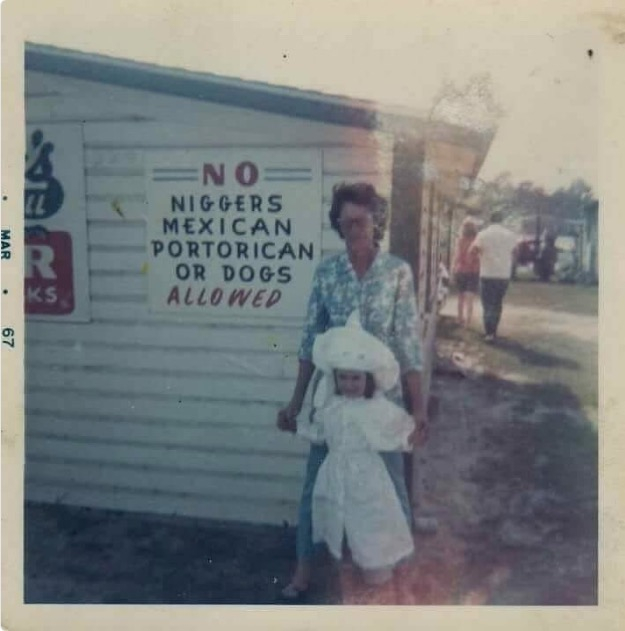

I was completely startled by this old photo. I am certain that it was from the southern US but still it hit me pretty hard. It was not that long ago. I was not yet 20 years old. White privilege still exists. White privilege is still ugly.

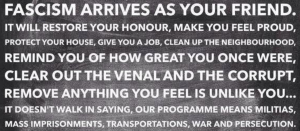

I found the following article helpful in thinking about the Nazi demonstration in Charlottesville VA this past weekend. In tribute I will be including the words of Heather Heyer as the closing of every one of my emails for the foreseeable future: “If you're not outraged, you're not paying attention." Heather should have a monument.

An open letter from the great-great-grandsons of Stonewall Jackson - - Jack Christian and Warren Christian

Dear Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney and members of the Monument Avenue Commission,

We are native Richmonders and also the great-great-grandsons of Stonewall Jackson. As two of the closest living relatives to Stonewall, we are writing today to ask for the removal of his statue, as well as the removal of all Confederate statues from Monument Avenue. They are overt symbols of racism and white supremacy, and the time is long overdue for them to depart from public display. Overnight, Baltimore has seen fit to take this action. Richmond should, too.

In making this request, we wish to express our respect and admiration for Mayor Stoney’s leadership while also strongly disagreeing with his claim that “removal of symbols does [nothing] for telling the actual truth [nor] changes the state and culture of racism in this country today.” In our view, the removal of the Jackson statue and others will necessarily further difficult conversations about racial justice. It will begin to tell the truth of us all coming to our senses.

Last weekend, Charlottesville showed us unequivocally that Confederate statues offer pre-existing iconography for racists. The people who descended on Charlottesville last weekend were there to make a naked show of force for white supremacy. To them, the Robert E. Lee statue is a clear symbol of their hateful ideology. The Confederate statues on Monument Avenue are, too—especially Jackson, who faces north, supposedly as if to continue the fight.

We are writing to say that we understand justice very differently from our grandfather’s grandfather, and we wish to make it clear his statue does not represent us.

Through our upbringing and education, we have learned much about Stonewall Jackson. We have learned about his reluctance to fight and his teaching of Sunday School to enslaved peoples in Lexington, Virginia, a potentially criminal activity at the time. We have learned how thoughtful and loving he was toward his family. But we cannot ignore his decision to own slaves, his decision to go to war for the Confederacy, and, ultimately, the fact that he was a white man fighting on the side of white supremacy.

While we are not ashamed of our great-great-grandfather, we are ashamed to benefit from white supremacy while our black family and friends suffer. We are ashamed of the monument.

In fact, instead of lauding Jackson’s violence, we choose to celebrate Stonewall’s sister—our great-great-grandaunt—Laura Jackson Arnold. As an adult Laura became a staunch Unionist and abolitionist. Though she and Stonewall were incredibly close through childhood, she never spoke to Stonewall after his decision to support the Confederacy. We choose to stand on the right side of history with Laura Jackson Arnold.

Confederate monuments like the Jackson statue were never intended as benign symbols. Rather, they were the clearly articulated artwork of white supremacy. Among many examples, we can see this plainly if we look at the dedication of a Confederate statue at the University of North Carolina, in which a speaker proclaimed that the Confederate soldier “saved the very life of the Anglo-Saxon race in the South.” Disturbingly, he went on to recount a tale of performing the “pleasing duty” of “horse whipping” a black woman in front of federal soldiers. All over the South, this grotesque message is conveyed by similar monuments. As importantly, this message is clear to today’s avowed white supremacists.

There is also historical evidence that the statues on Monument Avenue were rejected by black Richmonders at the time of their construction. In the 1870s, John Mitchell, a black city councilman, called the monuments a tribute to “blood and treason” and voiced strong opposition to the use of public funds for building them. Speaking about the Lee Memorial, he vowed that there would come a time when African Americans would “be there to take it down.”

Ongoing racial disparities in incarceration, educational attainment, police brutality, hiring practices, access to health care, and, perhaps most starkly, wealth, make it clear that these monuments do not stand somehow outside of history. Racism and white supremacy, which undoubtedly continue today, are neither natural nor inevitable. Rather, they were created in order to justify the unjustifiable, in particular slavery.

One thing that bonds our extended family, besides our common ancestor, is that many have worked, often as clergy and as educators, for justice in their communities. While we do not purport to speak for all of Stonewall’s kin, our sense of justice leads us to believe that removing the Stonewall statue and other monuments should be part of a larger project of actively mending the racial disparities that hundreds of years of white supremacy have wrought. We hope other descendants of Confederate generals will stand with us.

As cities all over the South are realizing now, we are not in need of added context. We are in need of a new context—one in which the statues have been taken down.

Respectfully, William Jackson Christian Warren Edmund Christian Great-great-grandsons of Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson

For several years i have been loaning money through Kiva. Kiva is a non-profit organization with a mission to connect people through lending to alleviate poverty. Leveraging the internet and a worldwide network of micro-finance institutions, Kiva lets individuals lend as little as $25 to help create opportunity around the world. I am one of 1,363, 259 people who have loaned a total of nearly one billon dollars to thousands of people around the world. Individual loans are small, but are combined with the loans of many others to invest in small business in developing countries. I like to support women in these countries, and specifically those that are working to start or build grocery stores.

Have a look at Kiva. If I can answer any questions let me know. I think it is a very good way to contribute.

Nobody told me that I had named the song incorrectly for the past few weeks. Everybody - keep your eyes on the fries.